One of my favorite YouTube channels is Dude Perfect. They had humble beginnings as college friends who spent more time planning trick shots than they did in the classroom, but have since grown to be one of YouTube’s most popular channels. (Their most popular video is actually a series of water bottle flip trick shots, but if you somehow haven’t heard of them - clear a few hours of your schedule to binge their content. It’s super fun.)

In addition to trick shots they produce various comedic sketches, one of which is called Cool, Not Cool. In this segment, each dude brings a random item that the other dudes vote on to determine if the item is, you guesses it, cool or not. The goal is to bring an item that every other dude votes as cool - thus earning the title of a super cool item.

This segment has always struck me as a parody of an investment committee at a venture capital firm. Just like the process described above, at an investment committee1 each partner has the opportunity to bring a company that the other partners vote on to determine if it is investment worthy or not.

The main difference, of course, is that “cool” is not the main criteria by which investors judge a company. But perhaps it should be (I’ll come back to this later).

Non Consensus Right

If “cool” isn’t the criteria for determining whether or not an investment is worthwhile, what is?

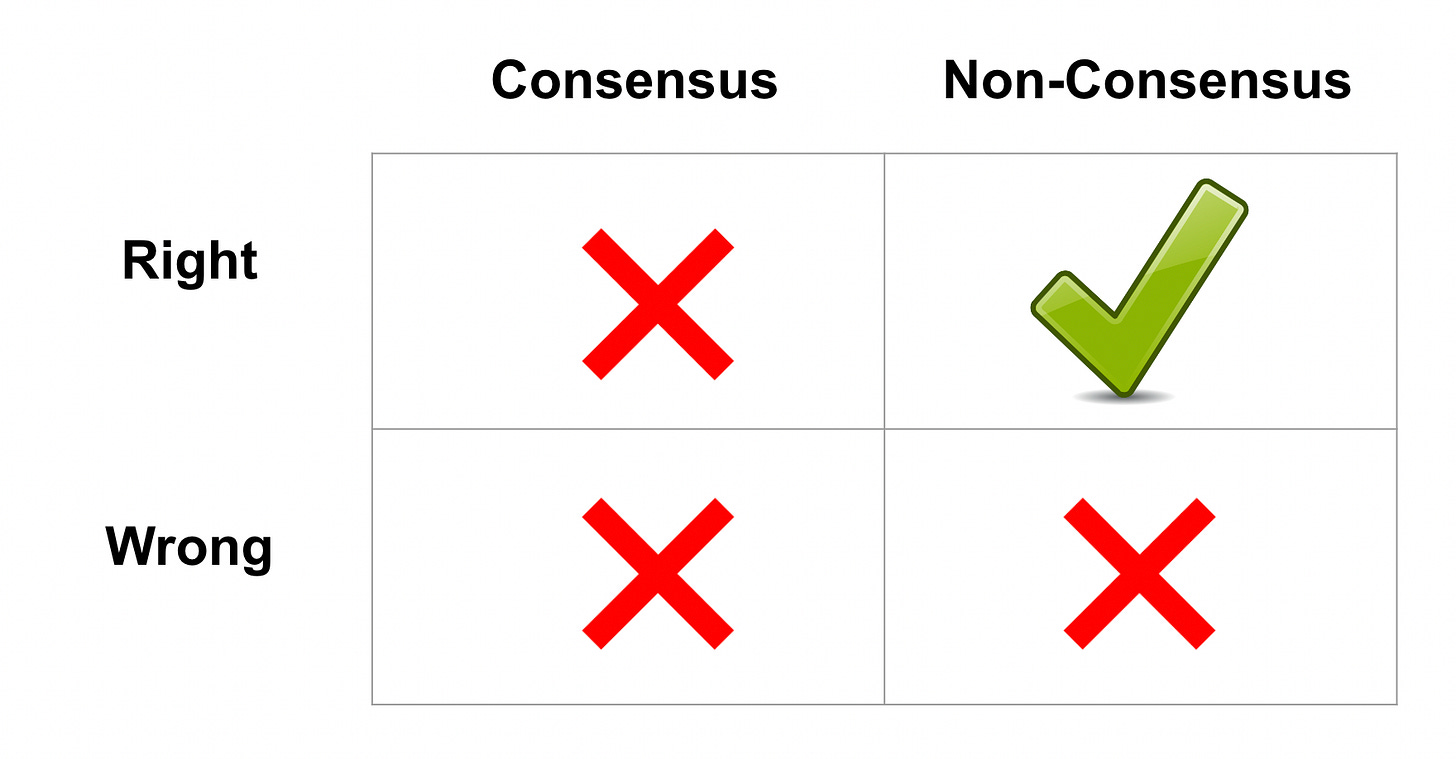

Well, there are many factors that go into an investment decision. But one of my favorite frameworks for thinking through an investment is the below 2x2 matrix that is attributed to Andy Rachleff .

Every investment is judged both at the time of the investment and in the future based on the outcome of the investment. At the time of the investment, an investment can either be consensus or not, and in the future an investment decision can either be right or wrong, depending on the success of the company.

Here’s a quick breakdown of the matrix:

Consensus and Wrong

The majority of the firm and the ecosystem viewed this investment as worthwhile. Therefore, even when the investment turns out to be a dud no one will question the decision retroactively. However, it doesn’t provide any returns due to its lack of success.

Consensus and Right

The majority of the firm and the ecosystem viewed this investment as worthwhile and indeed the company turned out to be a success! However, since at the time of investment it was a consensus bet, the entry price was likely too high to net a true venture scale return.

Non-Consensus and Wrong

The majority of the firm and the ecosystem questioned this investment and deemed it a mistake. And when it ultimately turned out to be a failed company the reputation of the investor is severely damaged.

Non-Consensus and Right

The majority of the firm and the ecosystem questioned this investment and deemed it a mistake. But when it ultimately turned out to be a success, not only was the investor vindicated but more importantly the investment led to outsized returns due to lack of competition and cheap entry price.

The basic gist of this matrix is that the only real way to make truly great venture scale investments is to make non-consensus and right bets. To do that though, you need to consistently be taking non-consensus risks - which is difficult because it could lead to detrimental consequences for your reputation.

This idea is can also be defined as Thielian contrarianism, and is discussed in various forms by some of the best investors of our generation.

In fact, I think it’s fair to say that it has become consensus that the only way to make money in venture is to make non-consensus and right investments.

The most important question then, is how do you consistently make non-consensus and right investments?

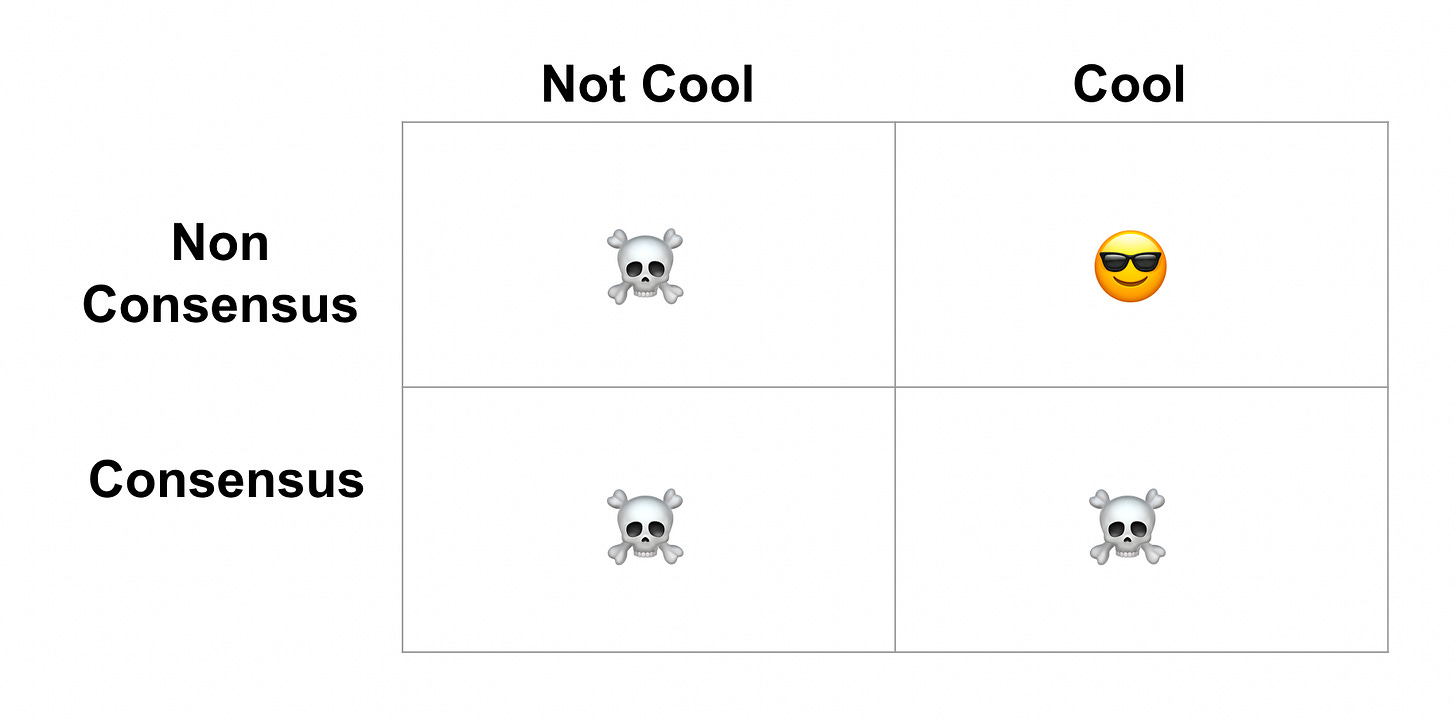

Cool and Non-Consensus

This is where the Dudes from Dude Perfect can help us. What I propose below is another 2x2 matrix that should be used in parallel to the consensus matrix above.

“Cool” as a concept, of course, is subjective. While some people might think of Danny Zuko2 or some other Hollywoodized depiction of a desirable individual, each and every one of us considers different things to be cool.

And while it may be the easiest path to focus on the things that are consensus and cool, having the courage to lean in to the non-consensus parts of your life that you find cool is what leads to the best outcomes. (Kevin Kelly’s “1,000 True Fans” is a relevant call out here.)

As a young investor this is challenging! The song stick to the status quo3 often pops in to my head when I’m excited by a company that isn’t classic B2B enterprise software.

But I firmly believe that an investor’s ability to be an additive investor is directly related to how passionate they are about the company. And what are people passionate about if not the things that they consider cool.

If You Wanna Be Cool Follow One Simple Rule

A few weeks ago I listened to an interview with Ted Weschler, one of Warren Buffet’s lieutenants at Berkshire Hathaway. In it, he discusses the need to consume different content than what everyone else is consuming in order to be a successful investor.

Using the non-consensus and right framework, this checks out. Truly unique investment decisions come from having insights that others do not, and the only way to develop those insights is to fill your mind with a myriad of material.

And so while there may be pressure to read The Wall Street Journal or Financial Times every day, or to attend AWS re:invent, I make sure to make time to watch the latest Dude Perfect video, to read the latest Brandon Sanderson novel, to listen to my favorite comedians’ podcast and to visit warehouses of ecommerce merchants to better understand the financial and logisitcal pains of our supply chain.

The simple rule that I follow is to pay attention to what I find to be cool. Because even if I end up being wrong, at least I’ll have had the opportunity to be non-consensus and right.

There are various types of investment committees at funds. Certain funds require a consensus vote in order to approve an investment, others require a majority and others (TLVP included) don’t require any formal approval other than an individual partner’s desire to invest. Furthermore, some firms have only senior partners on the investment committee, some have all partners, some have outside advisors and some include junior investment team members as well. Regardless, the absurd parallel with Dude Perfect should still make sense.

While Grease is a classic, it’s always disturbed me that the conclusion of the movie is: don’t be true to yourself. Put on a leather jacket and smoke a cigarette if you want to have a happy life.

High School Musical succeeds where Grease fails